Even in the dirtiest rivers there is life: The macroinvertebrates that reveal polluted waters

- Maria José Bu

- Sep 8, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2025

In our beloved Honduras, we often see large rivers like the Ulúa, Chamelecón, and Choluteca and think: “That river is so dirty!” And it’s no wonder—all the anthropogenic activities that reach these rivers are countless: deforestation, land-use change, fires, wastewater discharge, livestock ranching, agriculture, among others.

By “trained eye estimation,” we can tell when a river is polluted by its color, turbidity, viscosity, and especially by its smell. Today we want to introduce some biological indicators that we can find in these polluted rivers: aquatic macroinvertebrates! In this article, we’ll focus on indicators of poor water quality, so that if you ever encounter them in your water sources (hopefully you don’t!), you can say: “This river is polluted, because I found these little critters.”

In a previous article we told you about macroinvertebrates. To refresh your memory, “macros” (as we fondly call them) are aquatic invertebrates that can be seen with the naked eye and spend part or all of their lives in water. But why does finding them determine whether water quality is good or bad? Are there groups that tolerate pollution while others do not? The answer is that certain groups thrive in waters where oxygen, temperature, and nutrients (among other factors) are balanced, while others dominate in the opposite conditions.

Water quality—good or bad—can be determined through a biological index. A biological index is a measurement that uses living organisms to assess the ecological status of a site. In our country, we don’t yet have an index adapted to our rivers, so we usually rely on indexes from neighboring countries like Costa Rica (BMWP) and El Salvador (IBF), which share some similarities in physicochemical conditions and in the diversity of aquatic macroinvertebrate families.

Before we begin, we want to emphasize that some of these organisms can also be found in clean waters, but the difference lies in their abundance. In polluted waters, they appear in much higher numbers.

Coleoptera, Beetle (Family Gyrinidae)

Known as “whirligig beetles” because they spin in circles when swimming in still pools. They have the peculiar feature that, when seen from the side, it looks like they have two eyes on each side—four eyes in total! But don’t be fooled—they don’t actually have four eyes (Figure 1). Rather, it’s an adaptation that allows them to see both above and below the water’s surface¹.

Odonata, Damselflies (Family Coenagrionidae)

Damselflies (Figure 2), as these dragonflies are commonly called, are found in all types of waters, and polluted waters are no exception. It seems these insects prefer high temperatures and lowland areas² ³, and it is often under these conditions that the water is most contaminated.

Coleoptera, Water Scavenger Beetles (Family Hydrophilidae)

We also have the “water scavenger beetles,” which feed mostly on decomposing organic matter. They are excellent swimmers but prefer to stay near emergent vegetation. The adult (Figure 3A) looks like a typical beetle, but the larva (Figure 3B) looks quite different and can be difficult to identify, even for taxonomists (scientists who classify, identify, and name organisms)⁴.

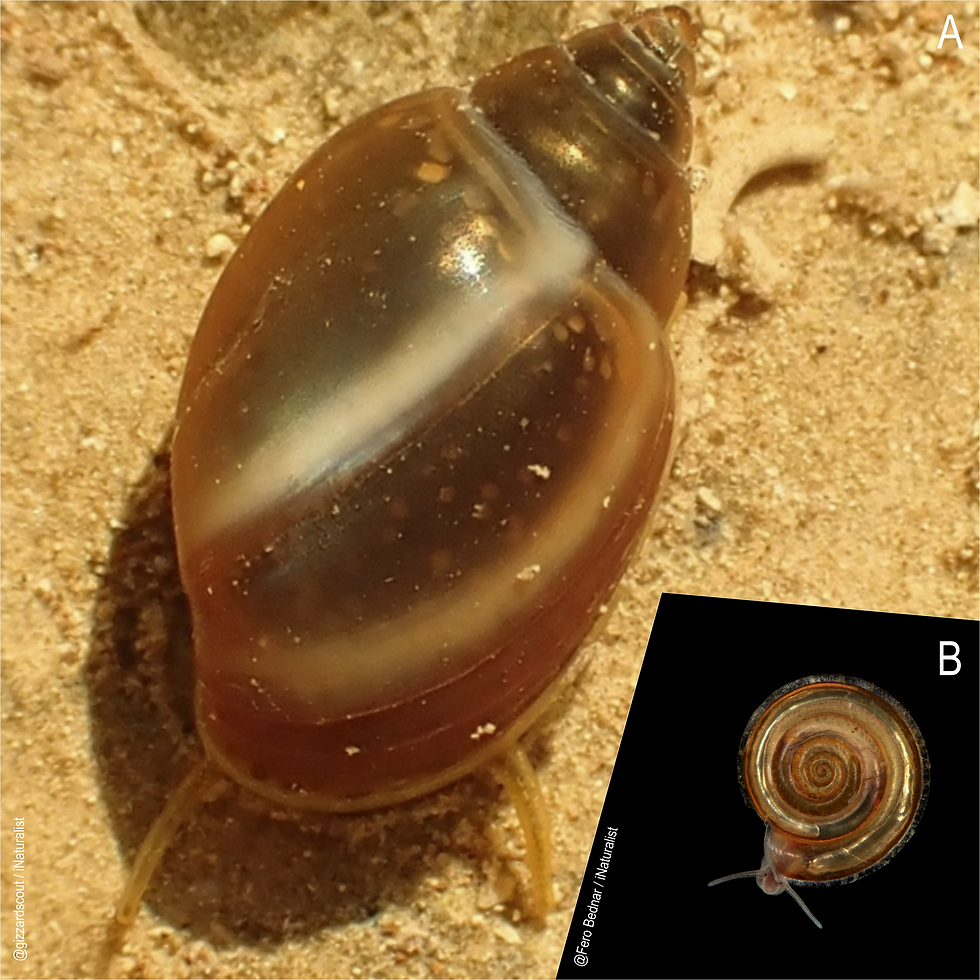

Gastropoda, Snails (Families Physidae and Planorbidae)

Snails are “filter feeders”—they feed by filtering organic material from the water. Finding certain types of snails in rivers (Figure 4) is not always a good sign. Their abundance, which often occurs in polluted rivers, indicates a high amount of suspended organic matter. The more organic matter is suspended, the murkier the water becomes, which blocks light penetration. This raises temperatures and reduces oxygen levels. Snails usually inhabit slow currents, pools, or ponds—ideal places to attach to fixed substrates.

Midges (Family Chironomidae)

As we near the end, we have these little “worms” that come in different sizes and colors. We usually find them beige in color (Figure 5A), but some are red (Figure 5B). This is because they are so well adapted to low-oxygen conditions that they have developed hemoglobin in their blood (hemolymph), allowing them to store and transport oxygen⁵.

Rat-tailed Maggots (Family Syrphidae)

These are rare to find, but “rat-tailed maggots” are medium-sized fly larvae that typically live in muddy areas. They are transparent, yellowish, or whitish in color (Figure 6A-B) and can be identified by their retractable posterior tube (the “tail”), which they use for breathing⁵.

Aquatic Worms (Subclass Oligochaeta)

Finally, we have the champions of polluted waters: aquatic worms, which look similar to earthworms. These small worms (Figure 7) decompose organic matter and obtain oxygen by burrowing into the substrate, creating air bubbles. They are abundant in anoxic conditions, deep areas, and eutrophic sites⁶.

If you’ve made it this far, you may have noticed that polluted water conditions are often linked to slow-moving areas of rivers, pools, or places beneath vegetation. This is because polluted rivers carry a heavy load of sediments and organic matter, resulting in murkier, denser water.

If you can’t spot these organisms with the naked eye in rivers, streams, or pools, I invite you to grab a kitchen strainer (make sure it’s one you won’t use again!) and scoop among the rocks, sand, mud, or vegetation—you’ll be able to see these aquatic macroinvertebrates. And if you find some, take good photos, contact us, and we’ll help you identify what you’ve found.

Finding these organisms in abundance is a “silent cry” from the rivers, reminding us that we must change bad habits and, above all, take care of our rivers. Next time you think about river pollution, remember it’s the tiniest and most ignored organisms that warn us first of the damage.

By: Maria Jose Bu, Biologist

Follow us on social media:

Instagram: @Honduras_Neotropical

Facebook: @HondurasNeotropical

E-mail: hondurasneotropical@gmail.com

_________________________________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Benetti, C. J., Michat, M. C. y Archangelsky, M. (2018). Order Coleoptera: Introduction. En Thorp and Covich´s freshwater invertebrates: Keys to Neotropical Hexapoda. (fourth ed., Vol. III, (pp. 607-811). Elsevier.

Urrutia , M. (2005). Riqueza de especies de Odonata Zigoptera por unidades fisiográficas en el departamento del Valle del Cauca. Boletín del Museo de Entomología de la Universidad del Valle, 6(2).

Ramirez, A. (2010). Capítulo 5: Odonata. En Springer, Monika & Ramirez, Alonso & Hanson, Paul (Ed.), Introducción a los grupos de Macroinvertebrados. (primera ed.) (pp. 97-136). Revista de Biología Tropical.

Arce-Pérez, R., Arriaga-Varela, E., Novelo-Gutiérrez, R. y Navarrete-Heredia, J.L. (2021). Giant water scavenger beetles Hydrophilus subgenus Dibolocelus (Coleoptera: Hydrophilidae) from Mexico with description of two new species. Zootaxa, 5027 (3), 387–407. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5027.3.5

Fusari, L.V., Dantas, G.P.S. y Pinho, L.C. (2018). Order Diptera. En Thorp and Covich´s freshwater invertebrates: Keys to Neotropical Hexapoda. (fourth ed., Vol. III, (pp. 497-603). Elsevier.

Benbow, M. (2009). Annelida, Oligochaeta and Polychaeta. En Likens, G. E., (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Inland Waters, (Vol II). (pp 124-127). Oxford: Elsevier

Comments