Casabe, Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

- Mario Ardón

- Dec 21, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 24, 2025

On this occasion, we move a little away from the biological to come closer to the cultural. Hand in hand with our esteemed guest, Mario Ardón, we delve into a story full of tradition and memory, where casabe is not just food, but heritage, identity, and emotion.

This article is the result of the author’s field accompaniment work in ethnographic research and development initiatives since the 1980s, based on his participant observation in Garífuna communities along the Caribbean coast of Honduras and several fieldwork seasons carried out from then to the present.

How is casabe prepared?

Casabe flatbreads are a Caribbean-Arawak culinary tradition, taken up and recreated by the Garífuna people. They are made from cassava flour obtained through a complex process that begins with cultivation and continues with the grating of the tuber on special graters. These graters consist of wooden boards—generally made of mahogany—with small flint stones embedded in them, known in the Garífuna language as egui. The grated pulp is then placed in a ruguma or culebra, made from fibers of bayal or balaire (a creeping palm from which very strong fibers are obtained), where it is squeezed to extract the liquid and obtain the flour (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. A: A: Collaborating in the sifting of cassava flour in a gibice or sieve made from balaire palm fibers. B: The sifting process. On the left, the container with flour to be sifted; on the right, the container with flour already sifted and ready for baking casabe.

The flour is spread on a boulu or container made of mahogany or cedar wood to proceed with sifting. With this finely sifted flour, casabe flatbreads are made on the burén or griddle. The flour is evenly spread over the burén and cooked quickly on both sides until a firm tortilla is obtained, which is then broken into crackers—initially into two halves of the circle, although it can be divided into quarters or further fragmented, producing square crackers and others shaped like half-moons. The breaking of the casabe is done according to preferences and transportation and distribution needs, especially when it is not for family consumption but for sale.

Casabe as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

In December 2024, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the knowledge and practices of casabe production and consumption as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity¹. This recognition honors a pre-Hispanic tradition that has survived among South American Indigenous peoples, Afro-Caribbean communities, and Central American cultures, where this food has been produced and shared interculturally for centuries. The five countries that jointly nominated casabe to UNESCO were the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela, and Honduras.

Casabe is more than food: it constitutes a complex of ecological, cultural, and economic practices. Its durability allows it to remain usable for long periods as long as it does not become moist. Proof of this is that during their long voyages across the Caribbean, conquistadors carried it aboard their ships as a safe food supply. In the book The True History of the Conquest of Nueva España², Bernal Díaz del Castillo mentions it more than one hundred times, evidence of its importance in the diet of Indigenous peoples.

The casabe production process

The production of casabe has relied on multiple varieties of bitter and sweet cassava. Many have disappeared, and today production depends on commercial varieties. In Honduras, processing methods remain essentially traditional. Small changes have been incorporated to lighten and facilitate the work, but the cultural structure of the process remains intact. In countries such as the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Haiti, and Venezuela, casabe is still produced for consumption and sale; however, the traditional processes documented among the Garífuna of Honduras are no longer maintained.

Until the 1980s, it was common to find instruments identical to those used during the time of contact and the colonial period. In Garífuna homes, a special roof beam was designated to hold the ruguma or “snake” (called zambucán in Cuba), made from fibers of the creeping palm known as balaire. Among the Tolupan and Garífuna peoples, this name is preserved, while mestizos know it as bayal (Desmoncus orthacanthos; Figure 2), highly valued in heavy-duty basketry. The traditional kitchen was set up with three stones that supported the burén or clay griddle, where the cassava flour—already pressed and sifted—was skillfully distributed to form the casabe flatbreads. Later, metal griddles were introduced, without significantly altering the procedure.

Figure 2. Bayal or balaire plant (Desmoncus orthacanthos). The Garífuna may have adopted it from the Tolupan Indigenous people, who use the same name for this palm. It is a creeping palm that produces very long and resistant fibers, used by mestizo and Indigenous communities for high-strength, durable basketry.

Hiyú, a variant of casabe flatbread

Alongside casabe, hiyú survives—a thicker flatbread made from the flour that does not pass through the sieve and remains from each sifting batch (Figure 3). It can be eaten as a snack or used to prepare a beverage of the same name, highly valued among the Garífuna.

Figure 3. Hiyú, a thicker and more golden version of casabe.

Casabe as a product of sociocultural significance for the Garífuna

The production of casabe in Garífuna communities of Honduras is a collective act loaded with symbolism (Figure 4). Women cultivate the cassava, transport it to the home, peel and wash it. They then call friends and neighbors for the grating process: using the egui grater over a large mahogany boulu or trough, they grate the cassava while singing traditional or improvised songs in the Garífuna language. This moment is festive, one of camaraderie and intergenerational transmission of knowledge and practices; observing the collective grating is witnessing a manifestation of the vitality of a living culture.

Figure 4. Group of Garífuna women gathered to grate cassava. In this space, traditional songs are sung. The trough placed on the floor is the boulu, and the boards on which each woman grates the cassava are the egui or graters.

Evolution of the casabe production process in Honduras

Over time, innovations have been incorporated: motorized mills partially replacing manual grating, mechanical jacks to press the pulp, and redesigned stoves for more uniform heat. Gibices made of balaire for sifting, rugumas, mahogany boards, and brushes remain in use, sustaining the continuity of the tradition (Figure 5).

Today, casabe maintains special value among Garífuna and mestizo populations. It has gained space in gastronomic tourism, although artisanal and semi-industrial production barely meets local demand. In communities such as Río Esteban, municipality of Balfate, Colón, it is produced in semi-industrialized forms, while in more remote places—Ciriboya and Batalla in the department of Colón, among others—more traditional forms of production and consumption are preserved.

Cultural manifestation of casabe

Casabe remains a highly valued food among Garífuna and mestizo populations, with different meanings and modes of consumption. For the Garífuna, it is associated with being eaten as an accompaniment to other traditional dishes such as various types of soups, while in other sectors of the population it is toasted and spread with different types of butter or simply consumed as an occasional snack.

The UNESCO declaration opens concrete opportunities. It is not only about protecting food-related knowledge and practices, but about revaluing a system of knowledge deeply rooted in the identity of peoples. The cultural complex of casabe can be integrated into territorial planning as a resource and opportunity for environmental restoration, social cohesion, and economic development. Its revitalization ensures the continuity of an ancestral tradition and offers a horizon of cultural articulation, educational and communication applications, with multiple possibilities to become a sustainable livelihood looking toward the future.

Figure 5. The stove most similar to those used by Caribbean Arawak peoples is built on three stones placed on the floor, supporting the burén or griddle for baking casabe flatbreads. This version has now been replaced by improved stoves built on a raised platform, reflecting a supposed improvement in the process.

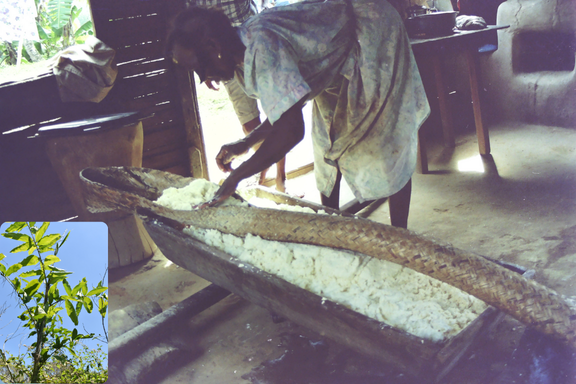

Figure 6. Anciana garífuna con boulu con harina de yuca recién extraída de la ruguma.

By: Mario Ardón, anthropologist

All photos belongs to Mario Ardón.

Follow us on social media:

Instagram: @HondurasNeotropical

Facebook: @HondurasNeotropical

Tiktok: @hondurasneotropical

E-mail: hondurasneotropical@gmail.com

_________________________________________________________________________________________

References

1. UNESCO. (2024). Traditional knowledge and practices for the making and consumption of cassava bread (Nomination file No. 02118). UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/traditional-knowledge-and-practices-for-the-making-and-consumption-of-cassava-bread-02118.

2. Diaz del Castillo, Bernal (1979) Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. (2 tomos) 44 y 318p, Promesa, México.

Comments