Captivity and sacrifice of jaguars at Copan: What are isotopes telling us?

- Diego Ardón

- Sep 17, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 26, 2025

We are all composed of different chemical elements. In humans and most living beings, carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen make up 96% of our bodies. The rest is made up of trace elements such as the calcium in your bones or the iron in your blood. But have you ever stopped to think where those elements originally came from? You might have come up with the answer: your diet. Every atom (Figure 1) of carbon in your body was once part of a chicken or a cow, and before that, part of a kernel of corn or a blade of grass—and if you go even further back, from the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that plants converted into tissue through photosynthesis. By understanding this transfer of elements through the food chain, scientists have developed ways to use the proportions of stable isotopes of different elements to reconstruct the diets of organisms that lived hundreds of years ago.

What Are Stable Isotopes?

If you remember your general chemistry class, you know that an atom is made of three subatomic particles: electrons, neutrons, and protons. The term isotope refers to atoms of any element that have a different number of neutrons. The number of protons gives each element its atomic number (for example, hydrogen is 1, carbon is 6, oxygen is 8). Electrons, meanwhile, interact with other atoms to form chemical compounds. Now to the point: neutrons. Unlike the other particles, neutrons have no charge, and when an element varies in its number of neutrons, it gives rise to different isotopes of that element, each with a different weight.

You may be more familiar with the term radioactive isotope, these are unstable isotopes that decay and transform into other isotopes over time. Carbon-14 is the most commonly used radioactive isotope to calculate the age of objects that were once part of a living being. Stable isotopes are the opposite: they remain constant in their number of neutrons regardless of time, and they vary predictably as they pass through the tissues of different organisms. These properties make them natural biomarkers, capable of recording the natural processes they take part in.

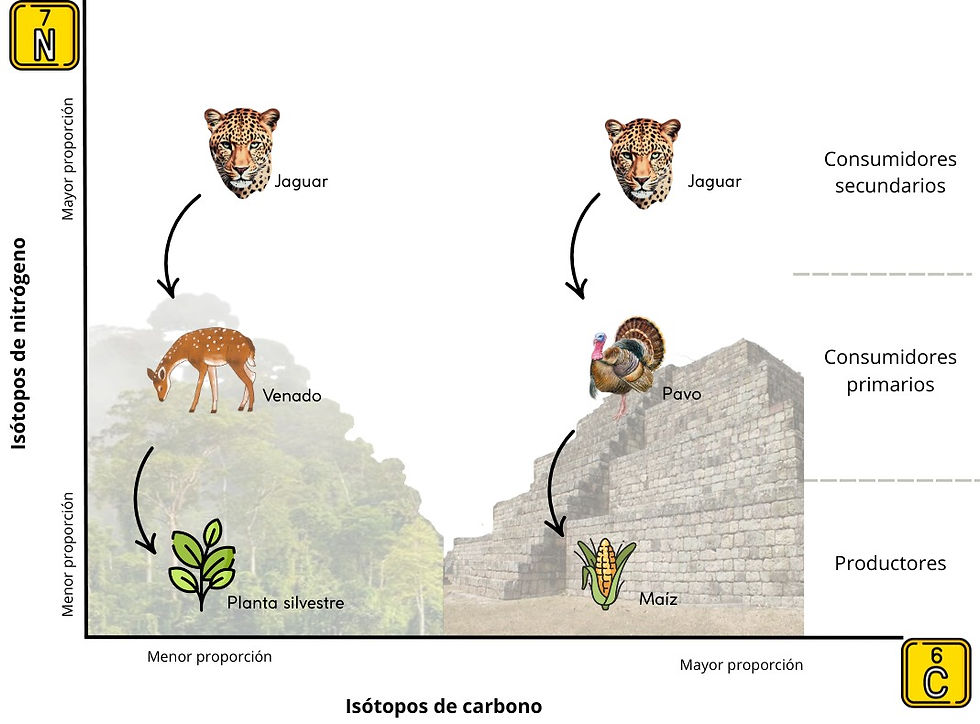

In ecology, the most commonly used are carbon isotopes, since they provide information about the origin of the primary producer—that is, the plant at the start of the food chain. Another frequently used stable isotope is nitrogen; the proportion of heavy isotopes gradually increases every time it passes from one organism to another. This gives us an idea of where an organism is positioned in the food chain. Oxygen isotopes are also used, though less frequently; they vary depending on the water consumed during the organism’s life, reflecting the region’s climate patterns. Differences in oxygen isotope ratios can reveal where an organism lived and whether it moved away from its place of origin during its lifetime. Amazing, isn’t it?

Using Isotopes to Study Honduras' Past

A very illustrative example of the use of stable isotopes in scientific research, and one especially relevant for us Hondurans, is the work conducted by U.S. researchers in Copán Ruins¹. The city of Copán was one of the most important centers of the ancient Maya civilization, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980. It flourished during the Classic period from the 5th century until its abandonment in the 9th century, lasting 200 years longer than we have existed as an independent nation. Excavations began only in the 19th century, and although much has been studied about the city and the Maya civilization in Copán, many questions remain unanswered.

Without a time machine, archaeologists depend on reconstructing the past through architectural remains, hieroglyphs, tombs, and biological remains. In 2018, the results of an analysis of animal remains found in ceremonial tombs in Copán revealed fascinating details about wildlife management practices in the ancient world. Among the animals identified were deer, crocodiles, turtles, birds such as an owl, a hawk, a macaw, and even stingray spines. But without doubt, the most intriguing were the remains of large felines found around Altar Q. Altar Q is one of Copán’s most iconic sculptures, located in front of the stairway of Temple 16.

Temple 16 (Figure 2) is one of Copán’s most important structures (and also the tallest). It is thought to date back to the founding of the Classic Copán dynasty by Yax K’uk’ Mo’ (“Radiant First Quetzal-Macaw”) around 426 AD. It is believed to have served as his and his wife’s tomb, and it retained ritual significance throughout Copán’s history. Copán’s decline is partly attributed to a military defeat by its former vassal state Quiriguá (in Guatemala), where its ruler 13 Uaxaclajun Ub’aah K’awiil, known as 18 Rabbit, was captured and executed. By the end of the Classic dynasty, ruler 16, Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat (“New Son on the Horizon”), was likely witnessing the city’s collapse. In an effort to reaffirm his power, he commissioned Altar Q, which depicts all 16 dynasty rulers, including Yax Pasaj, shown receiving the symbol of rulership from none other than Yax K’uk’ Mo’ himself (Figure 3). Around the structure, archaeologists found the remains of 15 large felines (at least six of them jaguars), sacrificed in honor of each of the previous rulers². This event must have been the equivalent of hosting a World Cup or the Olympic Games.

But how easy is it to gather 15 jaguars for sacrifice all at once? Even more puzzling, how could this have been done when deforestation and environmental degradation around the city are often cited as causes of the civilization’s collapse not long after this ritual? Here’s where stable isotopes come in. The remains of these animals provide clues about how they were gathered, unknown pre-Hispanic practices, and possible connections between Copán and cities hundreds of kilometers away. The study revealed that not all remains were jaguars—there were nearly as many pumas, and even a smaller feline such as an ocelot or jaguarundi.

The feline remains buried at Altar Q show carbon isotope signatures indicating a maize-based diet rather than one based on wild plants. You might wonder, were these felines vegetarians? But remember: carbon isotopes trace back to the producers at the start of the food chain. These felines weren’t eating wild deer that fed on wild plants; they were probably eating turkeys or domestic dogs fed on maize (Figure 4). Nitrogen isotopes confirm their high position in the food chain. Archaeologists interpret this as evidence that the Maya practiced feline captivity. A burial dating 300 years earlier than the Altar Q sacrifice shows a puma with this same dietary signature, suggesting the practice of captivity lasted for centuries (Figure 5).

We now know that Copán had historic ties to Teotihuacán in Mexico, where evidence of captive felines has also been found. Records indicate that Yax K’uk’ Mo’ visited Teotihuacán, and researchers believe he may have witnessed captive management practices there, later applying them in Copán. Oxygen isotopes in the Copán remains also show that some felines came from distant regions, suggesting a network for moving animals, or at least their remains, throughout Mesoamerica.

This study illustrates how stable isotopes work and what kind of information can be inferred from them. They shed light on Copán’s past, its inhabitants, and the animals they valued. Finally, they make us reflect on wildlife management, as the ritual sacrifice of these key ecological species did not prevent Copán’s collapse, on the contrary, it may have contributed to the region’s environmental decline.

By: Diego Ardón, Biologist

Follow us on social media:

Instagram: @Honduras_Neotropical

Facebook: @HondurasNeotropical

E-mail: hondurasneotropical@gmail.com

Cover photo from iNaturalist by @africaollienaturalist

_________________________________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Sugiyama N, Fash WL, France CAM. 2018. Jaguar and puma captivity and trade among the Maya: Stable isotope data from Copan, Honduras. PlosOne 13(9): e0202958.

Fash WL, Agurcia Fasquelle R. 2005. Contributions and controversies in the archaeology and history of Copán. En: Andrews EW, Fash WL (eds.). Copan: The history of an ancient Maya kingdom. School of American Research advanced seminar series.

Comments